A discovered object, called the Fuente Magna, and the Pokotia monument indicate that the Sumerians may have visited South America in the past.

The possibility that the writing engraved on the Fuente Magna was used by the Sumerians, and the identification of Sumerian place names in the Altiplano region, suggest that what today are Bolivia and Peru could represent the “Country of Tin to the West” or the “Land of the Dusk” of the ancient Sumerian inscriptions.

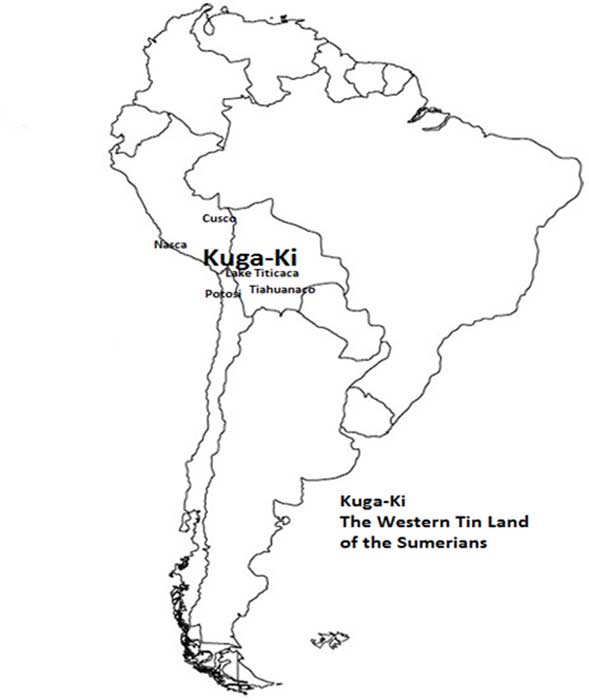

Kuga-ki

The Sumerians mention in their inscriptions a country to the west called Kuga-Ki from which they obtained valuable metals. Dr. AH Sayce states that “tin land” or “tin land” would be the translation of KUGA-KI in Sumerian. Sayce makes it clear that the Sumerians claimed to get their tin in that country.

The ancient Sumerians were great navigators. Sumerian ships sailed to Egypt, Northeast Africa and the Indus Valley in search of metals and merchandise to supply their industry with raw materials and satisfy the demand for the most popular goods among their people. Samuel N. Kramer, in his book The Sumerians, affirms that Egypt is called Magan in the Sumerian inscriptions, while the Indus Valley was called Dilmun.

King Sargon mentions in 2700 BC. Kuga-Ki was part of his empire. Professor Sayce, in an article entitled “Geography of Sargon of Akkad” and published in Ancient Egypt magazine, translated a document written by an Assyrian official from the 8th century BC. The document states that the empire of Sargon I included “the countries from where the sun rises to where it sets, which Sargon the […] king conquered by his hand,” and among many other lands “the Country of Gutium , »« The country of the Muru (Amorites) »and (Kuga-Ki)« the country of Tin that extends beyond the Upper Sea (the Mediterranean). »

Sayce believed that Kuga-ki was probably in what is now Spain. But the finding of the Fuente Magna suggests that Kuga-Ki was in South America and not in Spain. Since Kuga-Ki is located to the west of the Mediterranean, it is likely that it was the name of some region of North or South America, since the American continent extends to the west of the Mediterranean Sea, while Spain is right on the shores of the Mediterranean.

AH Verrill and R. Verrill, in Ancient Civilizations of America, and J. Bailey in Sailing to Paradise, argue that the area around Lake Titicaca could have been called Lake Manu by the Sumerians. According to these authors, tradition has it that the Sumerians made many visits to the lands west of the Mediterranean that they called Kuga-ki. These traditions make it clear that the Sumerians sailed to Kuga-Ki in their Magur ships. In the cuneiform texts written on tablets it is stated that the Magur ships could carry up to 18.5 tons of precious metals.

Mining operations

The Sumerians possibly first discovered the road to Kuga-Ki thanks to the Atlantic currents that lead from Africa to Brazil. The first Sumerian explorers probably reached Brazil and traced the Amazon to find large deposits of tin in Bolivia / Peru. The main center for mining in this region was, and is still today, Potosí.

Once the Sumerians began their mining operations in Kuga-Ki, the natives probably began to work on their mining operations and adopted many Sumerian customs, expressions of their language, and the social technology of writing, that is, the Proto-Sumerian alphabet. This would imply that writing would have had a long tradition among the Bolivian / Peruvian peoples, as Clyde Winters writes in his book Ancient Scripts in South America .

The Andes: the ancient kingdom of the Antis

The Andes could have constituted the “Country of Tin” or Kuga-Ki of the Sumerians. The Andes mountain range was originally called Antis. The region was known in the past as Antisuyo, the Kingdom of the Antis. This was also the land of the Antis Indians. In the Quechua language, spoken by many indigenous people in the area, “antis” means copper. Antis was also the name of the native peoples that formerly inhabited this South American region.

The word “Antis” is probably not of Quechua origin. The Chipaya language, another indigenous language spoken in the area, is different from Quechua and Aymara. Some researchers believe that Chipaya is closely related to the Mayan languages spoken even today in Mexico.

This region of Bolivia is famous for its mineral wealth. Many of these metals are found in the Bolivian highlands, near Lake Poopó, an inland sea that was once linked to the Pacific Ocean by ancient rivers that dried up.

The Bolivian Altiplano is the largest plateau in the world. It houses two inland seas: Lake Titicaca and Poopó. This high region of the Andes mountain range makes it a suitable location to be Lake Manu, the “Lake of the Clouds” of the Sumerians in which metals were extracted from the Dusk Mountains, the lands located west of the sea. Mediterranean.

Lake Poopó is 80 kilometers long. Formerly it was surrounded by mountains and canals on all sides. Satellite photographs reveal that in the past there were deep channels in the vicinity of Lake Poopó. It is a sea of salt water only a few meters deep and that at times has dried up.

Lake Titicaca and Poopó are connected by the Desaguadero River. The companion lake of the Poopó was the Uru. The city of Oruro was located near Lake Uru.

Riches in the mountains

Among the metals that can be found in the vicinity of Lake Poopó are copper, tin, gold and silver. Here are the metals obtained in the cities of Oruro and Corocoro, where gold and copper were extracted. The names of these cities suggest a Sumerian origin. In Sumerian the word uru means city. The suffixes – gold in the cities around Lake Poopó are strikingly similar to the Sumerian term “uru.”

It is also interesting to note that one of the main mining centers in the region is Potosí. Potosí is famous for its tin deposits, and in its surroundings is Mount Catavi, formed by solid tin.

The Potosí region was in the past an important mining center. In the 1550s, the Spanish began to extract silver from Cerro Rico, in Potosí. As a result of the Spanish attempt to fully exploit the wealth of this mining area, a “terrible” number of Indians died in the mines. Hugh Thompson vividly describes this tragedy in his book The White Rock: An Exploration of the Inca Heartland.

Thompson describes how the mine consumed the labor force of the Bolivian Altiplano. Those who did not die were oppressed by the miserable wages they were paid. In a single generation, the population used in mining operations in this area of the Altiplano was reduced by half. In the next generation it was halved again. And Potosí was still demanding his tribute. “

In modern history, Potosí continues to be a mining center for the extraction of tin, copper, lead and silver. Located near Tiahuanaco, Potosí could have hosted a Sumerian settlement in ancient times, perhaps the cities of Oruro and Corocoro. Bailey suggests that the Potosí toponym could be related to the Sumerian term Patesi, which means “priest king.”

The metals extracted in the Altiplano were transported along the Pilcomayo River (to the Río de la Plata). It is possible that the Sumerians transported the metals obtained in Bolivia across the Atlantic to ancient Sumeria. An excellent route for the shipment of tin from Kuga-Ki followed the course of the Rio de la Plata, crossing the Atlantic to the east and up the Cape of Good Hope towards the Indian Ocean until it reached the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea.

Symbols

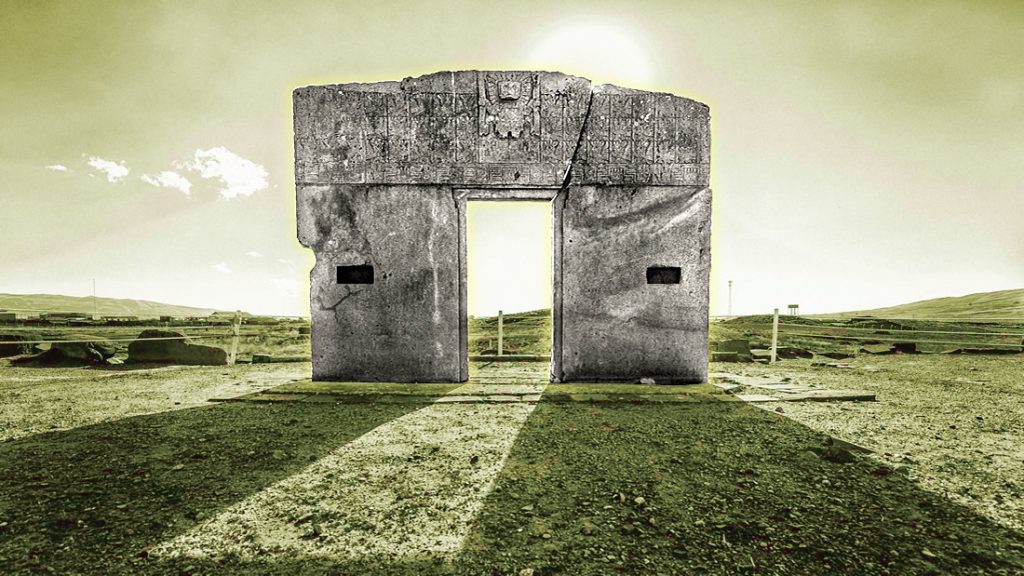

In addition to the affinity between the symbols found in the Pokotia monolith, Fuente Magna and some Inca textiles, we also observe that these symbols are identical to the signs engraved on the Mochica bricks. A common feature of carved Inca huacas or stones are steps carved directly into the rock.

Clyde Winters demonstrates in Ancient Scripts in South America: The Sumerians in South America that the Inca Throne, an immaculate low-step carving, is similar to Proto-Sumerian symbols. Other signs of the huacas or carved rocks of Rodadero and the White Rock of Chuquipalta are strikingly similar to the writing found in Pokotia and Fuente Magna.

In addition to the Sumerian influence on ancient South American writing systems, it is interesting to note that the Pokotia statue and the Tiahuanaco monuments feature similar headdresses, as well as rib-like markings across the chest. This coincidence reveals the relationship between the builders of these monuments.

In the South American region where the mythical Kuga-Ki was probably found, the Aymara language is spoken. There are Aymara words similar to their Sumerian equivalents. This fact is not surprising after deciphering the inscriptions on the statue of Pokotia and the Fountain Magna. These documents reveal that the Sumerians brought various aspects of their religion to Bolivia.

Linguistic evidence confirms the idea that the Sumerians living in Kuga-Ki were miners. The Sumerian term for copper was Urudu; this word agrees with the Aymara words for gold (“ouri”) and copper “anta, yauri.” The similarity between these terms suggests that the Sumerians may have been the first Old World people to exploit the metal mines scattered throughout the Titicaca region in what is now Bolivia.

The presence of Sumerian words in the Aymara language, the Sumerian place names in South America and the Sumerian writing of the Fuente Magna and the statue of Pokotia show that the Sumerian civilization spread in the past through South America. This leads me to deduce that present-day Bolivia and Peru could have formerly constituted Kuga-Ki, the “Country of Tin to the West” mentioned in the Sumerian inscriptions.